24-10-2017

Meeting with Karin

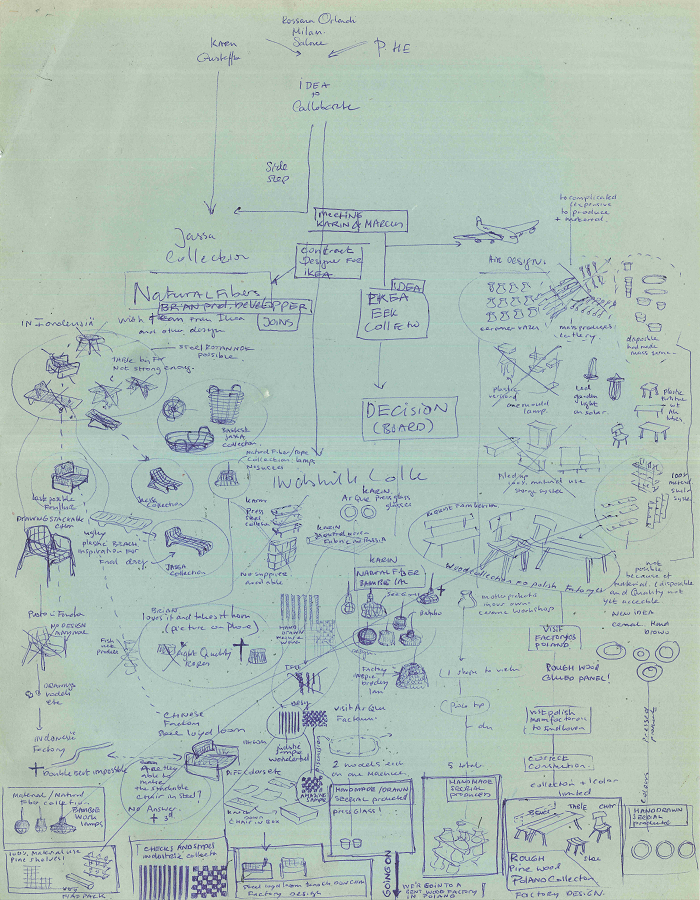

Years ago, during the Salone del Mobile in Milan, I met Karin Gustavsson at Rossana Orlandi where we always present our work. It was an unusual meeting because it was full of energy from the very first moment. This scene was repeated in subsequent years, as we became increasingly more enthusiastic about a possible collaboration. If we generated so much energy just from talking to each other, imagine what it would be like to actually work together?

At a certain point the decision was made: we would start working together. No problem as Karin, in her position, is able to commission external designers. The question was whether I wanted a contract for the project, or a contract to work as permanent external designer. With a contract for a project we would agree one fixed amount. As permanent designer you can be asked to work on any kind of project and can declare your hours. It was also mentioned that they wouldn’t be monitoring the hours too closely so you could essentially work as many hours as you wanted. So for the money, it was not interesting to sign a one-time contract.

And within the framework of sustainability, I have become more aware of the fact that long-term collaborations may make much more difference than trying to be more economical. You can profit from the knowledge that has already been gained. Working together is largely investing in each other and getting to know each other. So you only have to do this once. If it is no fun or doesn’t work, you can still always decide to stop, but with a permanent contract you can get to work without having to think about the finances every time. IKEA does not offer payment per item sold, so in that sense there is no advantage in large quantities.

We got started straight away with a task for the Jassa collection for which I, together with other designers, mostly from IKEA, was to design a collection. My designs would therefore become part of the whole. We were of the opinion that a collaboration, as well as being continuous, should also make an impact and we thought that we should make an entire Piet Hein Eek collection.

This was an unusual idea, as IKEA had until then only presented solo collections by designers in the PS collection but these were more product focused. We really wanted to make a varied collection that would be distributed over all divisions in terms of materials and functionality. I came up with a theme that had been in my mind for a while: ‘hand made – serial produced’. This is a concept in which the first models are made by hand and then used to make moulds, which in turn are then used to produce large quantities. Furthermore, we kept in mind that the collection should show respect for materials and traditional crafts.

Karin organised a meeting in Älmhult, the place where Ingvar Kamprad was born, built up his business and to where he has also remained loyal. Älmhult is a tiny place in Southern Sweden and the fastest way to get there is to fly to Copenhagen and then take the train for another few hours. Or you get picked up and brought back by taxi, that also happens regularly. Älmhult is to IKEA what Eindhoven was to Philips. It even has its own IKEA. Älmhult is probably the smallest place in the world with its own branch of IKEA. But the boss doesn’t want to cut ties with his roots by moving the business to a larger city as many of the employees would like. He finds it important that his employees all know who they are working for, so what is better than walking through the shop where the designs are presented and sold and where you can meet the customers; a compulsory visit to one of the purpose built shops round the corner. The funny thing is that everyone sees how useful this is and is happy with it.

Along the corridor leading to the canteen, which is actually a kind of giant conference room with a gigantic sweeping stairway, are also individual meeting rooms. We landed in one of these rooms with Karin and Marcus Engman, the creative director of IKEA. It was here that we discussed the plan to make an IKEA-Eek collection. I explained to Marcus that I really wanted to create a handmade ‘mother’ shapes from which we could subsequently make moulds just like with ‘normal designs’ in order to ultimately make large quantities. The advantage was that the costs would primarily only be in the development phase, and that the production would remain pretty much the same and so the consumer price would also remain the same, so that affordable ‘handmade’ products would be available on the shelves. During this conversation we discovered that, just like with Karin, communicating about a design went very smoothly. Where we operate on a small scale, organising the whole process from idea to customer, IKEA does this on a large scale. What we have in common is attention for all the possible aspects that are involved in the process from idea to consumer.

Marcus was instantly on board. He had been thinking for years about the possibilities of making products in large series’ yet at the same time retaining a unique character. He was enthusiastic and prepared to present the plan to the board. It would be a task that didn’t fit within the existing structure. It later turned out that there was hardly any or no difference and that the whole structure, which was seen as leading, was much more flexible that had been thought. Karin was able to commission the project within her budget so that it was not important into which division the products fitted. It seemed like an enormous change but in practice this was not the case.

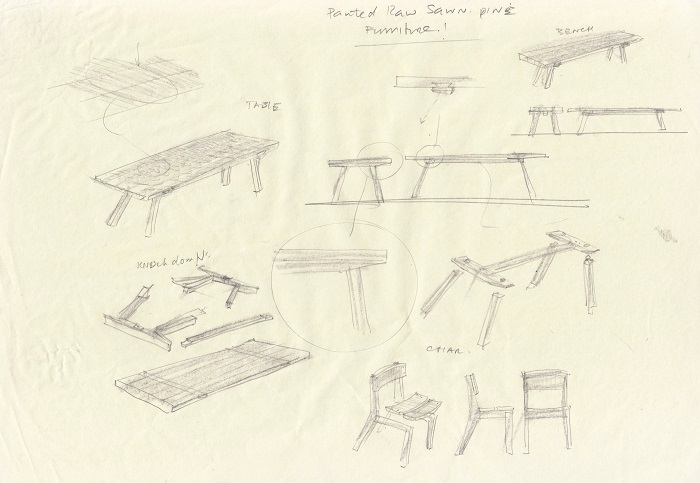

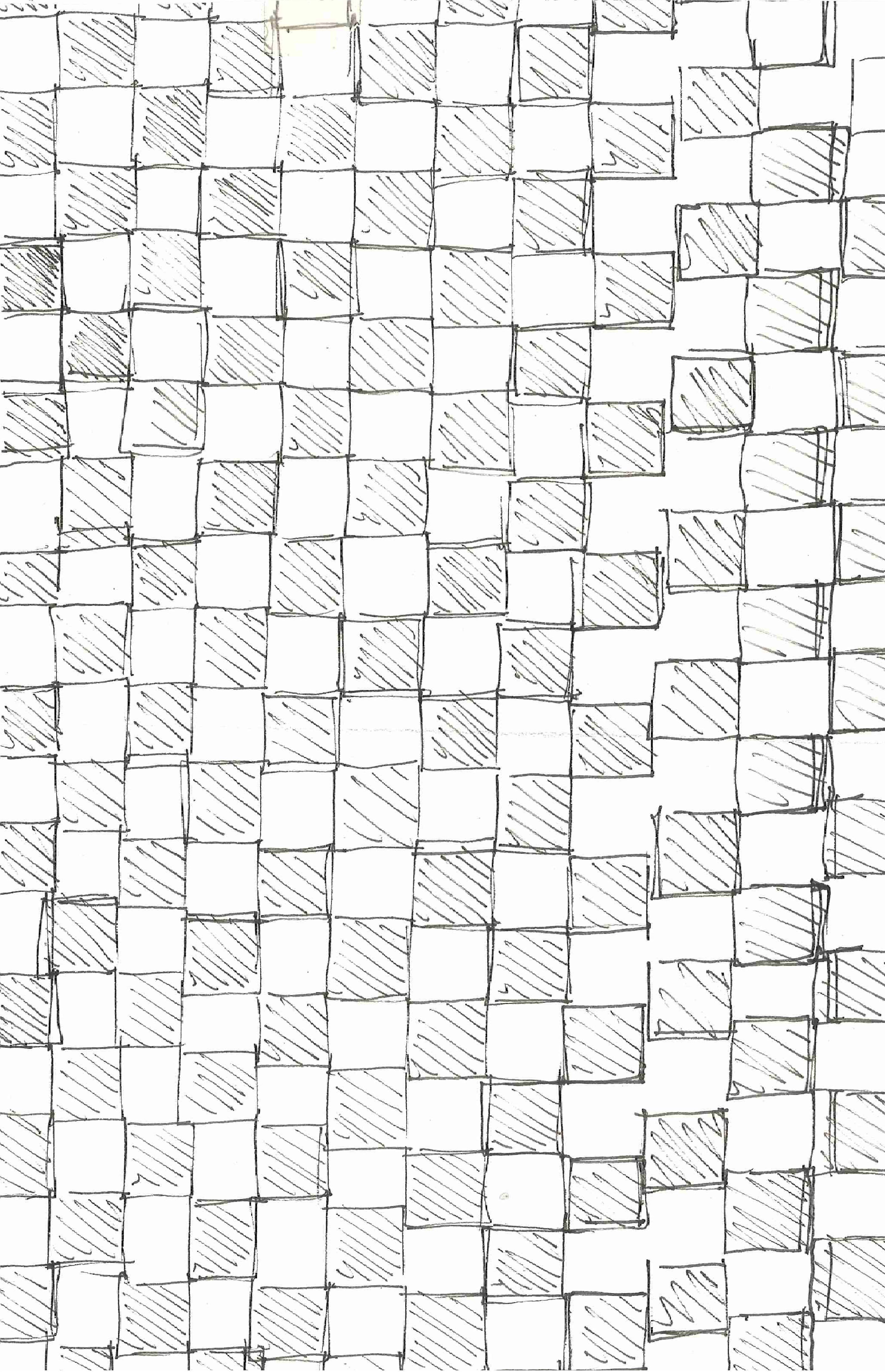

In the plane on the way home I sketched a series of designs in my notebook. The starting points were ‘hand made – serial produced’, do not throw away and making new designs from pine to reverse the decline of the Polish wood factories. From a historical perspective, the wood factories in Poland were considered to be very important. The first IKEA products were mostly made of pine, but when the first IKEA branch burned down, the Polish factories delivered new stocks free of charge, so that the fire did not result in the premature end of IKEA, but the start of a long-term collaboration. For decades the wooden products were important to the turnover and growth of IKEA but nowadays, furniture made of smooth pine has gone out of fashion. I was asked if I could use this wood to create a different image and feeling. Once home, I put my first series of designs down on paper and sent them to Karin. Now it was a waiting game whether we would be given a green light from Marcus for a true IKEA-Eek collection.

The contract

Karin had already sent me a sample contract. It included two choices: either design for IKEA on project basis or as IKEA designer; IKEA doesn’t do royalties. I thought: would other, bigger designers get royalties? But I quickly realised that it is not so strange that a company that makes products as affordable as possible in large quantities chooses not for royalties but for the true cost price. They pay an honest hourly rate and that’s how it is. But anyone who has ever worked for an hourly rate knows how tricky it is to declare all your hours. It is quite simple at IKEA. The hours you work are paid at the agreed price; it is simple and straightforward. You may not become a millionaire but it really is a nice way to work.

The contract also included a secrecy clause. I told Marcus that I found this clause challenging because, as a general rule, I can’t keep my mouth shut and end up telling everything to anyone who will listen. So it would not be realistic for me to sign this secrecy clause. I also expressed my doubts about the use of the clause: wouldn’t it be better for a company like IKEA, that is big and strong and has nothing to fear, to share instead of hide? I thought it would be good marketing to adopt open communication. Marcus answered that he was in complete agreement with me and that he had been trying for years to change the culture in this area. We crossed out the clause and signed the contract to create a whole IKEA-Eek collection.

Designs

While designing the new collection I was largely able to fall back on ideas I had developed earlier but that had never seen the light of day because they would need to be produced in such large numbers to make production cost effective. The IKEA quantities suddenly made this possible.

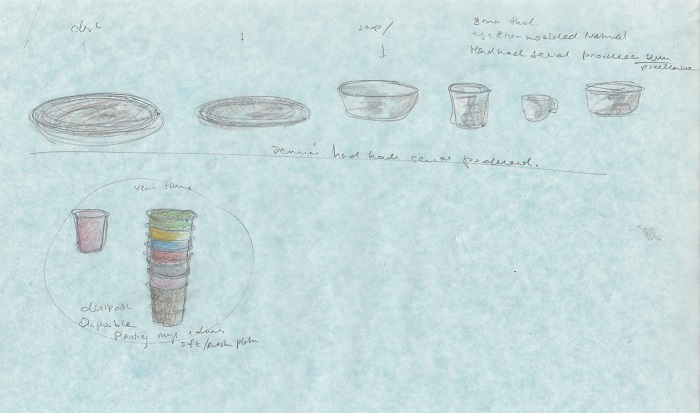

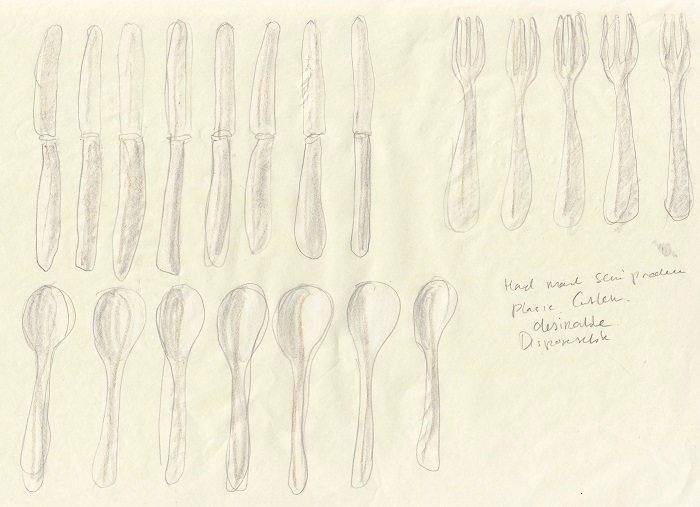

One of the ideas I had shelved a while ago was that it would be very easy to make disposable plastic cutlery, which would then not be thrown away because it has been made so well and so beautifully and whereby every knife and spoon is different. This kind of cutlery would be injection-moulded. A large quantity of spoons are injected under enormous pressure in a kind of Christmas tree structure. So why not use the same mould to make all kinds of different handmade spoons, forks and knives at the same time? Every few seconds 50 forks, and all of them different: this is the epitome of ‘hand made – serial produced’! I also had a similar idea for plastic (disposable) tableware.

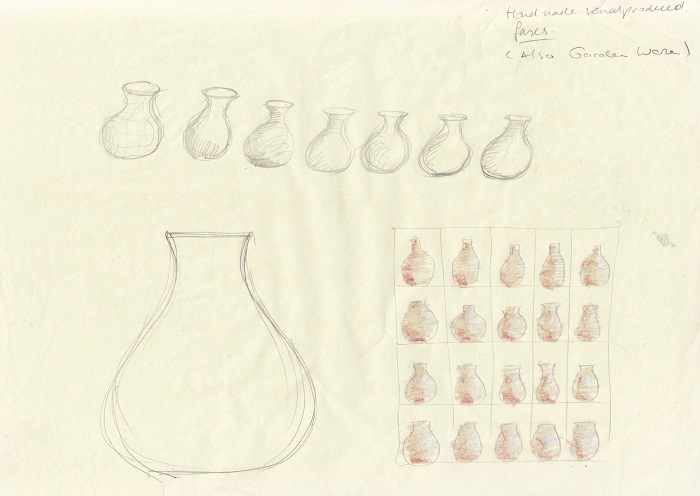

Handmade series production was the starting point for the six earthenware vases I wanted to make. Once again, we would make moulds of these handmade vases. Because they are round and always turned, it is difficult to see how many different models there are. Ceramic is always made from a mother form. This is used to make a mother mould which is then in turn used to make production moulds. So, as long as the quantities are large enough, you can just as easily work with several different mother moulds and the rest remains the same.

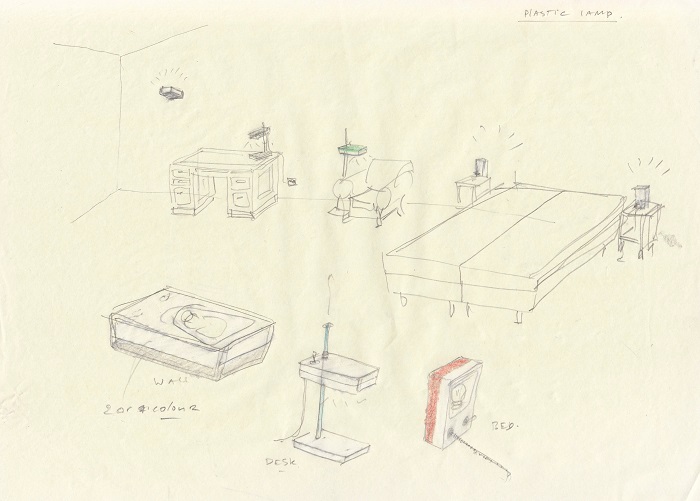

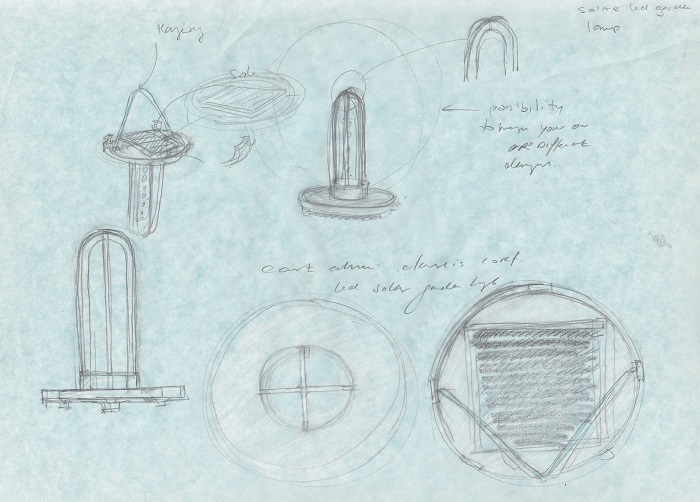

Karin called me to tell me that she actually also wanted some kind of garden lighting. Something using solar energy and with LED lighting. So I devised a cast aluminium lamp that can be hung in a tree or placed on a table, and turned upside down to recharge. I was also keen to work with injection-moulded plastic, because this is only feasible in large quantities. The single-mould lamp we make in ceramic was a perfect starting point to make a plastic version and I made drawings of plastic furniture. Karin later added several other materials for me to think about: bamboo lamps that would be made in Vietnam, linen goods from Russia and the chair that just didn’t make it into the Jassa collection would be made in China using steel and paper fibre.

The theme ‘do not throw away’ was almost one hundred per cent represented on the shelves cabinet. Only the wood removed by saw cuts and creating holes is taken away or burned. I had previously made a similar cabinet for a different project, but then very large and much too laborious. I liked the idea of giving the vertical planks on each side a different colour so that the cabinet has two faces. I devised sturdy wooden furniture for the factories in Poland.

Indonesia

We got started with the Jassa collection right away. For this, I was to make several designs for rattan furniture. The factories where the rattan products would be made are in Indonesia. So I eventually had to travel to Jakarta to visit these factories.

IKEA tried to keep as much rattan as possible in the collection so that the factories in Indonesia would have enough work and the traditional craft would be preserved. The factories are often central areas where numerous smaller home factories supply their component of the total production. In the factories, the products are developed, brought together and placed on transport. There are often whole villages whose existence depends entirely on one factory. The IKEA factories I visited are actually situated in very large buildings, from which items are also produced. In every case, there are incredibly large numbers of craftsmen and women dependant on the sales of rattan furniture and thus dependant upon the whims of the consumer in the international market. IKEA has given itself the goal of creating a constant demand so that this traditional craft is supported by the enormous volumes.

Travelling in Asia is always an experience, and this taxi journey from the airport was no exception. I had to share my attention between the enormous advertising boards along the roadside leading from the airport to the city, the city itself which was a veritable anthill of traffic, construction, food stalls, slums and tower blocks and the conversation with the Indonesian IKEA employee who had picked me up from the airport. She told me that she lived in Jakarta, had worked for IKEA for years and with her job was able to support her family. If you work anywhere for long enough, everyone seems to know everyone else. So wherever I travel to in the world for IKEA, I am always supported by a close-knit team.

We spent the night in a luxury hotel where we tried to make something of our breakfast in a gigantic conservatory with a huge group of elderly people. It was almost impossible to make ourselves understood among the chattering of the old people. And this was not the last time in Asia that we found ourselves immersed between the cheerful victims of elderly group trips. As soon as possible after breakfast we took a taxi to the station. The train journey was an experience in itself. The landscape and way of life there passed before my eyes like a movie.

The train stations are often buildings dating back to colonial times. My father spent his youth in Indonesia, on the same island. There’s a good chance he stood in the very same stations. After his detention in the Japanese camps during the Second World War he returned to the Netherlands with his grandmother and two brothers, but without his father. There was something to see almost everywhere along the track. It was a feast for the eyes and the imagination. Finally, after hours in the train, followed by another few hours in a taxi, we arrived at the factory. Indonesia is many times larger than the Netherlands and the roads and public transport much slower, so travelling always takes time.

When you visit a factory, you have to wake up early so that you can get started together with the factory workers. The following morning we arrived at the factory before dawn. For the first time I saw a typical ‘factory for IKEA presentation’, that I would later come to know as company culture. Such a presentation always takes place in a relatively modern office space with a suspended ceiling, often with glass walls and decorated with photos of the director-founder of the factory. In any case, a room in strong contrast with the rest of the building. The furniture is always Asian: luxurious. The tables are always loaded with food and drinks. In short, no expense is spared to make everyone feel comfortable, yet it is not all beautiful.

An IKEA factory presentation is always a PowerPoint presentation including lots of figures relating to production numbers, the materials and techniques, the possibilities, the turnover and the number of employees. This is all usually represented in pie or bar charts. If you’re lucky there will still be time, before lunch, to dive into the factory. And then the fun really starts of course. In the factories you get to see the materials, machines, prototypes, production methods and handicrafts and then the ideas start taking shape.

As the morning progressed I started to realise, it was a more or less organic process, that there was no way that the designs I had made could be produced. My designs were all based on a combination of steel and rattan. Now it turned out that they only wanted to work with rattan. Steel was not possible. I found this a little strange as there was an enormous number of prototypes hanging from the walls of the factory, several of which were made with a steel frame. It was the express wish of IKEA to avoid complicated products and so the whole product had to be made by the same supplier. The products had to be made completely of rattan.

I had one advantage. Because I had arrived last, due to my busy diary, we had shortened the trip and my visit was limited to two days. I should actually have arrived together with the other designers. Everything had been organised so that the rest of the designers were finished and all the prototypes were at my disposal. This was also a disadvantage now that it turned out that my designs could not be produced. I either had to adapt the existing designs very quickly or make completely new ones. My first reaction was to try to produce the designs completely in rattan instead of steel. The men were ready to get started straight away. It was wonderful to see how they skilfully crafted the first models with hand tools, usually with air pressure, and literally with their hands and feet. Most of the designs turned out to be far too weak without steel and we were even unsure whether they would have been strong enough with the steel components.

My designs often push the limits of what is possible. During the process in which we came to the conclusion that most of the designs were not realistic, I came up with several new designs, which hardly displaced the disappointment of the failure. Karin was nervous for a while but when she realised that the sketches were making their way in quick succession into the workshop, and that the guys were working well, everyone, including Karin, was relieved. The visit to the factory and being present on the work-floor actually panned out very well, as always. After a series of alterations, the only designs of mine that stood a chance were a chair that can be completely dismantled and a kind of reclining chair.

I was inspired to change the design for a daybed, which stood no chance without the use of steel, based on those ugly stackable plastic ones you find on the beach. We made a prototype of this bed completely in rattan. After we had made a good start in the right direction and everyone was becoming more enthusiastic, it turned out that the adjustable backrest yielded insurmountable problems. Precisely because it was adjustable and there was the possibility of trapping a limb between the moving parts, the bed was allowed, but would have to be made without moving parts. So basically, it was not allowed. That was, to put it mildly, disappointing because we had designed a super simple folding system in which the construction offered the possibility of setting the backrest in different positions. The overhang at the end of the bed also presented a problem. If you sat on the corner of the bed, the whole thing would flip up and you would end up on the floor – totally not dangerous, but unacceptable by IKEA standards.

In every IKEA development team there is one employee who specifically focuses on safety. From this employee’s field of responsibility, the design was rejected. Furthermore the bed was also on the large side, mentioned the logistics guy; it would not easily fit onto a large IKEA pallet. So we had to devise a smaller bed without adjustable backrest and without angled legs. When the product is finally ready, there is also someone who travels there especially to define the quantities. This may seem somewhat cumbersome, but it means that decisions can be made there and then and that all-important aspects are safeguarded. The employees regularly change functions within the company so that they have a good idea of each other’s responsibilities.

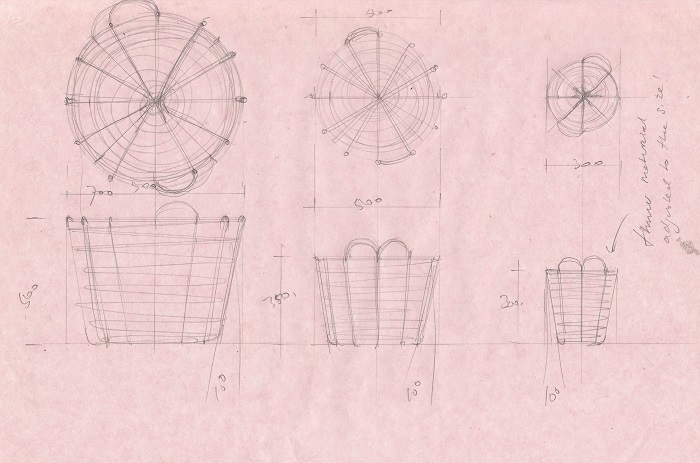

Meanwhile, I had adjusted the reclining chair, which was now made completely from rattan. By looking around and seeing all the things that were being made, and particularly also how the men were doing this, I had seen a detail that I loved the look of. They made the furniture from approximately 3 cm thick rattan. The frames were strengthened using diagonal connections of thinner rattan and the seat and back areas were filled in with woven fibres made from very thin rattan or bamboo strips. It was the pink-thick rattan I loved. By tapering the ends and bending around the thicker rattan, it was possible to assemble the pieces in a very beautiful way. I liked the idea of making all the products using this thickness, potentially combined with the thicker rattan. The overall appearance of the product without the woven fibres was constructive and had an almost African feel.

The pink-thick rattan also became the inspiration for a series of baskets. These were made as a spiral that begins in the centre of the base of the basket and circulates around the base and up the walls that, together with the vertical spines that also span out from the base, form the basket shape. The handles were made by connecting the spines together in a curve; two of the vertical spines bend to form a handle. The basket, the material, and the technique are one.

I showed Karin the sketch of a basket and asked her whether it already existed. She thought not so we were able to get started. On the evening of our departure, after two days’ work, we had finished prototypes of the baskets, a chair, a bed, a daybed and a lot of failed models. We all had a really great sense of achievement. I had also sketched the beginnings of a stackable rattan chair, which was pretty complicated and which I would later complete and send the finished drawings.

On the way back we stopped off at a batik shop to look at some fabrics. Karin had also asked me to do something with textile, yet time was slowly but surely slipping away and it seemed that we wouldn’t be able to fit it in. I have very limited experience with textiles and it is not my area of expertise. Personally, I don’t think that is a good reason to turn down a request and Karin did not seem worried at all.

During my time in Indonesia I became well acquainted with the IKEA factory and the people working there. Burt, the product developer, was a fun and really nice man to work with – smart and capable. And the knowledge and skills of the workers in the factory were enormous. What was also striking was that all employees had a scooter and seemed to work normal hours. Even more important: everyone was relaxed, happy and worked hard. All very well organised! In the taxi back to the airport I asked how things worked at IKEA. It turns out they have a code of conduct for suppliers that regulates the salary, working hours and also schooling opportunities for the children. The problem of not producing under poor working conditions seemed to be easily solved.

In the evening we drove back to the hotel and travelled back by train. The following day I wandered around Jakarta with Karin and Hedwig, the photographer who had travelled with us. It was easy to see the remaining presence of the Dutch colonial past. There were canals with buildings reminiscent of Amsterdam, but also true colonial constructions and even here and there something modernist, and all this alongside everything built after the liberation. An intriguing mixture of architecture. But for me, the most beautiful was the lack of maintenance. A little faded glory yet very dynamic and full of life. The most beautiful, oldest, and most raw part was perhaps the poorest neighbourhood towards the harbour, where the Dutch East India Company warehouses used to be situated. There was a little market in between the buildings. It was dirty and rather poor but they were dealing in real goods, so it wasn’t just poor. So there we were: two blonde Scandinavian ladies and a Dutch beachcomber. It was fun and inspiring and this shared experience helped us to understand each other better. If Karin did not already know, she found out then that I much prefer raw, broken and poor, and I find all this more beautiful than gathered wealth. We all agreed on this.

The stackable chair was delivered after several weeks. Everyone loved it. It was stackable and comfortable but I was not happy with it. It wasn’t what I had envisioned and it was actually not a very special object any more, which I really wanted it to be. I rejected the design and suggested making a better and more detailed sketch, which could then be used to make the chairs. Several days later we sent the drawings and work started in Indonesia. Time was now getting short as the definite designs had to be confirmed. As the quantities are so large, you need around six months for production but also another six months to distribute all the products to all the IKEA branches worldwide.

Brian Johnson, an American who once started at IKEA as a product developer and purchaser and has now worked for the company his whole life, has travelled all over the world and has a wealth of experience, also couldn’t manage it despite the new drawings. Brian is a little like all IKEA employees, but then in the extreme, a completely unique personality. Someone who has made a place for himself, works very independently, knows what IKEA is all about and respects this but does not work based on hierarchical, constrictive conditions. He does what he does independently in an organisation and for that organisation without losing strength or making personal concessions. He is practically always away from home and therefore a bit of a cowboy.

A double bend had to be made in order to produce the stackable chair. It turned out that this was not possible with rattan. Also, the stackability and the way in which the components fitted in with each other was not yet entirely clear. It seemed simple but was actually a complicated chair. In the end we all decided to start again and to make three-dimensional studies and models. An intern worked on it for a while but he also couldn’t figure it out so I subsequently asked one of our own guys to take a look, but he also had trouble combining all the essential aspects to make the chair beautiful, manufacturable and stackable. I thought that we would be finished within a day, but it ultimately took more than a week to create a working model in the computer.

I had thought that it was a very simple idea and product but now became aware of the fact that I had underestimated it. We sent the models and drawings to Indonesia but the bend remained a problem. I still think it could have been solved, but it was a little over the top to travel all the way to Indonesia just for a chair. In light of the deadlines, the stackable chair could not be made and ultimately the design in which we had invested the most time had to be shelved. Whether the chair is actually simple or not and whether I, not for the first time, in my optimism and enthusiasm have landed others with an unsolvable problem, we will only know if we ever actually decide to produce it.

The presentation

Even though we had crossed out the secrecy clause in the contract and I had told everyone who would listen in great detail all about what we were doing for and with IKEA, the marketing team in the Netherlands had different plans. They wanted to make a one-time announcement that we were working together and at the same time publish the first images. We had presented our own photos on our website and I secretly arranged with Karin that we had access to images but we didn’t make much impression. We actually had a lot of fun in, as agreed, going against these rules.

When the IKEA marketing campaign was launched we were completely surprised by the impact it had. I was invited on numerous television programmes and ended up at Umberto Tan, which I have known since the age of eighteen. This broadcast gave the already significant amount of attention an extra boost. All the national newspapers wrote pieces about the collaboration and everything went crazy, all because of IKEA’s announcement that we would be working together. The size of IKEA and the awe for such a big company meant that our collaboration was considered to be very special. I later realised that there was a kind of national pride about a Dutch designer working together with a company of this magnitude. Outside the Netherlands there was hardly any attention for our collaboration.

The Jassa collection was presented months later in the cornfields in the neighbourhood of Utrecht. It was the middle of summer but the bleakest day we had had in months. It was cold and raining almost constantly. I was picked up by taxi, and perfectly relaxed until I stepped out and discovered that it was taking place outside, but luckily they had provided training jackets. It was the intention that I would give a presentation about my furniture and our collaboration. The whole Jassa collection was displayed for the first time in style rooms in the cornfield. Despite the bad weather, an enviable number of people had turned up. Normally, if we really do our best, we are happy if one journalist attends our activities. IKEA has built up a reputation of giving very special presentations whereby they can be sure of throngs of journalists. I had never before realised how much size matters on all fronts. IKEA is a large company and that makes everything different.

For the attending Dutch press, it was my contribution that was important and so it received the appropriate attention. Due to this excessive attention, the content and nuance were pushed into the background. The idea soon emerged that the Jassa collection had been completely designed by me. The fact that it was only a bed, a chair and some baskets that I had designed, alongside all kinds of other products that were not my creations, was very difficult to communicate. They also thought that the Jassa collection was the Piet Hein Eek collection, even though this will be presented a year later, in the spring of 2018.

After several other speakers very seriously explained how well everyone was working together, it was my turn to say something. In the cold tent in the middle of the cornfield it seemed logical that I shouldn’t take things too seriously. I told a hilarious story about the culture and especially the size differences between IKEA and Eek and about the experiences we had had in relation to safety: that we had developed a swing chair and that when it was roughly finished, the safety employee pointed out that you could trap your finger under the swing and that we could make a swing chair but it could not swing. Or that a knot in a piece of wood can fall out, leaving behind a hole into which a child could stick its finger and with just the wrong movement that finger could easily be broken. So there can be no knots in the wood. On the other hand, if there is a hole in one of our pieces of furniture, and a child sticks its finger in it, it will probably result in the child being boxed around the ears and told to be more careful with the table. IKEA almost has to be afraid that a parent with bad intentions would break a child’s finger in a hole where a knot has fallen out so that they can claim compensation from IKEA.

If we sell a table with such a potential risk, we can be almost sure that nothing will happen because we sell so few, but IKEA sells such large quantities that a similar risk will almost certainly lead to an accident. So for IKEA, every risk is real and therefore unacceptable. The story was picked up and the most often used quote was that Eek doesn’t consider it important if a child breaks a finger in a knot hole in one of his pieces of furniture.

Industriell

Meanwhile, we were busy making prototypes and designs for the Industriell collection that will be launched in the spring 2018. The names for an IKEA collection are taken from a database. These names have undergone a testing procedure to be sure that they can be pronounced everywhere and do not have undesirable meanings in other languages.

By now the results, or lack of them, were becoming more clear. The plastic tableware could not be made because it was not actually possible to use degradable plastic to make a sustainable tableware series. Despite repeated attempts on my part, the aluminium lamp ran into opposition. I suspect that the expensive moulds and the serious development process had a deterrent effect. Actually, all the products that involved significant development and moulding costs were rejected, even though Karin herself had proposed most of them. We never even got started with the plastic chairs and table. The plastic cutlery, which would have created the biggest effect in terms of ‘hand made – serial produced’, was ultimately not produced. The aluminium lamp, the pressed metal shelving units, and the plastic one-mould lamp also didn’t progress further than the sketch phase.

It seemed that IKEA preferred to choose accessible techniques and processes in order to be able to develop cost effectively, efficiently and quickly. I was a little irritated at this way of working, because beforehand I had been looking forward to developing products that would normally, in terms of technique, be a bridge too far for us. I now also realise that IKEA launches new products every season with which it keeps the shops interesting. So the turnover rate is very high and therefore the need to control the development process is also great. It was a horrible thought to me that my designs would only be on sale for a few weeks, only to make place for a new collection. Why not include a product in the collection permanently? Surely it is a shame to put all that effort into making just one series?

At a certain point I realised that we have sold less than 5000 of our best selling chair in the last ten years and that IKEA makes thirty thousand units of on product at one time. So they make more chairs in one go than I would make of one product in my whole life. Their investment is therefore much more efficient than ours. This immediately also explains how the numbers make it possible to develop and introduce large quantities into the market with so much attention in such a short space of time and with such large teams.

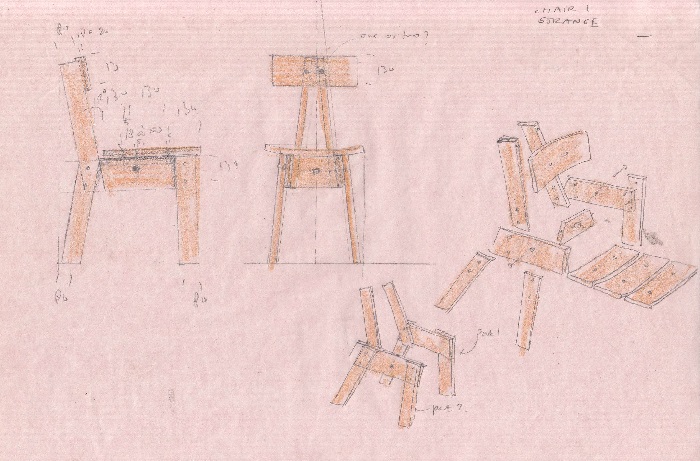

Of course we hope that some products will be included in the permanent collection. The pine furniture is most promising in that sense. Precisely because it was devised to break a downward trend, there is a serious chance that, if it sells, it will continue to be produced. The design for the chair is very unique and characteristic, a kind of all-or-nothing-design. If it is embraced it could even become an IKEA-Eek classic or, and the chance is small, it will be a complete disaster.

Polish wood

The task of designing pine wood furniture was very simple on one level. It had to be very different because the production methods that had previously been used had resulted in fewer sales. This downward trend had to be turned around. Instead of reducing production to meet the decreased demand and adjusting to meet demand, we wanted to change the market. It turned out that breaking with tradition had some basis in reality.

When we visited the factories in Poland, they had already made prototypes in one of the factories. They had done this with a certain amount creative interpretation. The various designs for the chair demanded the most attention, not only because the construction of a chair is very important but also because the cost price is most under pressure. You always need several dining chairs, so they cannot be too expensive. But the demands placed upon them are much greater than on a table, for example. Having recovered from the initial shock that it had all been made quite differently than I had sketched, we were able to say something useful about the models.

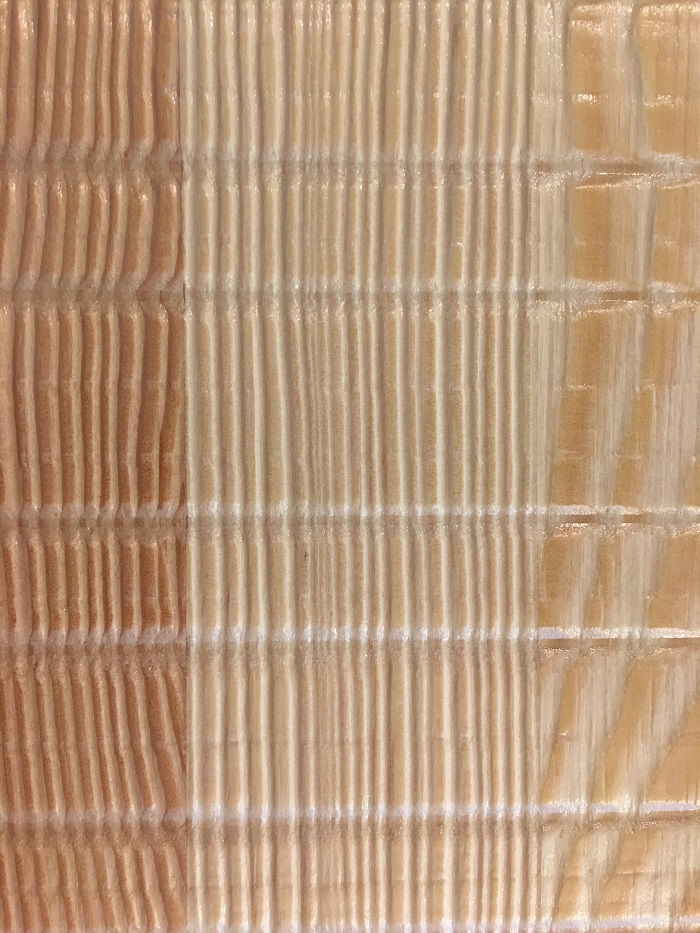

I wanted the wood to be roughly sawn, just like the first raw planks to come out of the sawmill. It was possible to make the chairs in this way but the large planks for the table-tops had to be glued and the knots removed due to the now famous finger-breaking-risk. We discussed the maximum size of the planks that could be glued and how rough the wood could be in order to produce the best possible result. Everything they had been trying their best to achieve for the past fifty years was now being questioned. Instead of smooth and perfect it now had to be rough and imperfect. At a certain point I thought it might be a good idea to take a completely glued panel right back in the process and coax it through the big band saw. Brian asked the men whether they could do this. After some hesitation we received an affirmative. Brain then asked them to do it there and then, we would go to lunch and look at the results after our break. The result was enchanting. We all felt the structure that was rough yet also soft and because the stroke of the band saw was so clearly visible against the grain of the wood, it disguised the seams where the planks had been glued together. We had found the solution: a rough wooden plank that felt pure and true and yet met all the IKEA product requirements.

It turned out that this was not the only bump in the road. In the subsequent phase the connections had to be made as I had designed. The pieces of furniture were all knockdown and the customer had to be able to assemble them as simply as possible with as few nuts and bolts as possible. I wanted to saw the wood diagonally and give it an edge so that the volume and the edge combine to provide rigidity and that the bolt is only needed to pull the components together. They had never done this before and in principle, only the solutions that have previously been tried (and intensively tested) are possible. So this means that something new or different is impossible and that less and less is possible because the standards are set increasingly sharper. Various meetings followed, as well as e-mail correspondence and special conversations, but without result.

At a certain point the Polish team was visiting us. Karin tried to get as many people as possible who were working on the collection to come to Eindhoven in order to increase the understanding for what we were doing. A recognisable discussion once again ensued. I explained that it did not make much sense to use too many screws and pins in pine because it is a soft wood and the connection I had devised was more robust. But they had never made anything this way, so did not believe me. After talking for over an hour, the Polish product supervisor asked the manufacturer if he could make the detail exactly as I wanted. The answer was ‘yes’, whereby she pretty much ordered them to go and make it instead of talking about it for so long. Luckily I got my way, because this was really an essential detail for the series. As well as the structure of the wood, the construction method was also something that would make the furniture stand out. We had already made a chair ourselves that I had tested in my own way, by sitting on one chair leg and using my whole body weight to twist in the chair. The chair survived the test brilliantly and I was sure it would be fine.

Hand drawn – machine woven

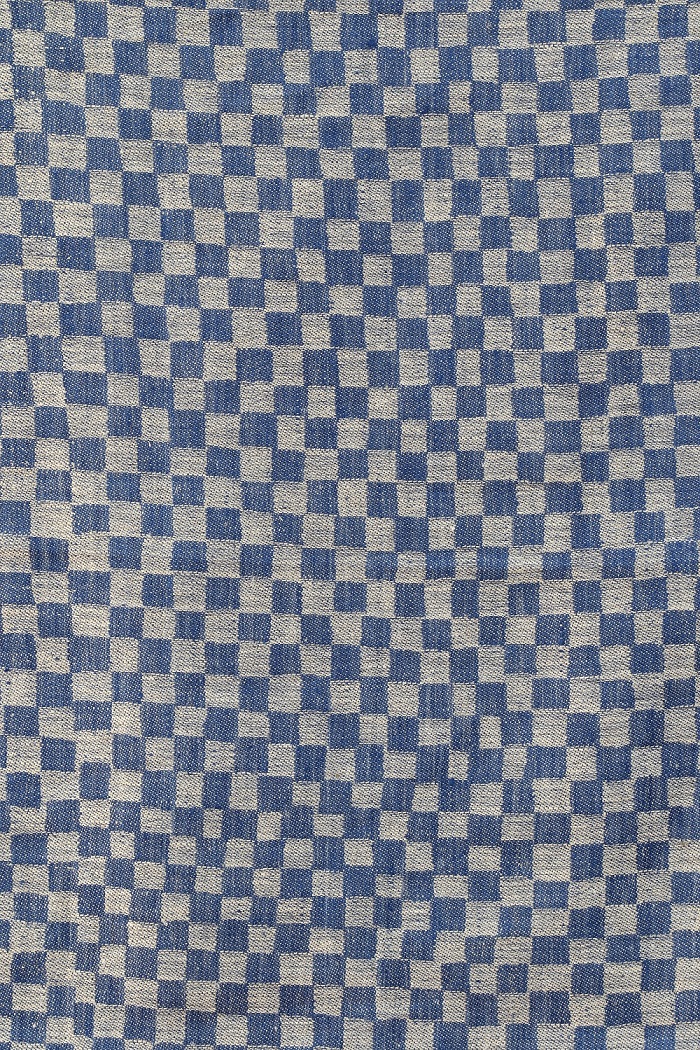

Due to all the other developments, I had been postponing the textile designs a little. Textile is far from being my speciality and none of the ideas I had sketched until then were interesting. I hadn’t come any further than a pattern design. With the deadline approaching and pressure rising I had a good idea. Using jacquard weaving looms it is possible to weave extremely complicated patterns. I decided that I could devise two patterns, within the context of ‘hand made – serial produced’, one with stripes and the other with blocks “checks and stripes”. If you do this by hand, you can be sure it will not end up straight. The checks were even a little clumsy. It took hours just to draw the design as neatly as possible and yet the result was deplorable, if the goal had been to produce a perfectly geometric pattern. But when the goal is to create something handmade, as with this collection, the result was beautiful. The only remaining question was what the patterns would look like after being woven.

As there are pattern designers walking around at IKEA, we decided to send the checks and stripes drawings to Älmhult, where they could turn them into a digital file that could then be sent to Russia. The first samples we received were, instead of smooth stripes, a little blocky. Instead of transferring the drawings in detail, they had worked very roughly with pixels, whereby the whole idea had become lost in translation. Nevertheless, the tea towel looked pretty good. However, I still wasn’t completely satisfied with the pattern because the width of the stripes varied. I figured that if you do your best to draw equally thick stripes by hand, it would be much more striking. So I drew a new pattern that we digitised ourselves this time.

When the result arrived several months later it was really beautiful. As the process had been rather difficult, Karin had decided that we would probably scrap the block design. But I actually considered it to be essential. All kinds of arguments went back and forth. We were already over the deadline. They couldn’t print two different fabrics. It was too expensive. But I knew that after making the design, the costs would actually remain the same and it wouldn’t make any difference to the factory. I suggested that we could make and send the digital files ourselves and that we would give it a try. Once again, Karin put her shoulder to the wheel and the job was commissioned. When the samples of the stripes and checks arrived, we saw just what a good idea it had been to persevere. The checks gave the impression that someone with an inferior handloom had really done their best to weave a lovely design. The pattern looks very handmade but is actually produced in large quantities on a superior weaving machine. In the end, the ‘hand made – serial produced’ theme can perhaps best be seen in the checked tea towel.

Asia

As well as the wooden furniture being produced in Poland and the textile being produced in Russia, most of our other designs were being made in Asia. In November 2016 I travelled to Asia for a lightning tour during which we would visit as many manufacturers as possible in a short space of time. As I had to be in Japan for a different project, it turned into an Asian trip with a very busy schedule. From Tokyo I flew to Shenzhen to continue the journey with Karin and Brian and the rest of the team. We had one or one and a half days per location. We started at the factory in China where the chair that had been rejected in Indonesia due to the only-rattan-story was being made with steel and Lloyd loom fibres. Lloyd loom is a technique that has recently become available to everyone due to the expiration of patents. It is a method in which the fibres are made by twisting together paper and metal wire.

The prototype had already been made but the backrest and seat had not been assembled at exactly the right angle. We carried out some tests by provisionally wedging the backrest and seat between the side panels and when we were happy with the result we had the frames newly welded. The colour combinations also still had to be defined. The manufacturer of the paper fibre had already travelled to the factory with his colour sample book to discuss the possibilities. I believe he had journeyed four and a half hours by car to come and give personal advise. We chose all kinds of colours but ultimately only one colour made it into the collection. It seemed that all the efforts had not been worth the trouble, but the opportunities this man offered were quite inspiring. It was fun working with the IKEA suppliers and presented lots of chances and possibilities as well as providing inspiration for considering whether we could also purchase and produce in Asia.

I saw a pipe-bending machine in the factory, which presented new opportunities. I thought that they could perhaps use this to make the impossible stackable chair, originally intended for the Jassa collection, with a steel frame. In the central space, which was no more than a roof in between two parallel buildings, there were beautiful sofas and we asked if they could make prototypes of these. I have never even seen the designs. They listened attentively and I think that, at the time, there was a true intention to get to work with these objects. But my enthusiasm was apparently too great for the organisations. They were probably only given a commission and budget for the design as it was planned, not for spontaneous designs. We had finally succeeded in getting the completely flat-pack chair in production. Everyone was really enthusiastic about it right from the start because it fits into a flat box when disassembled, but once put together it is a serious armchair.

The journey continued to Vietnam where we visited the factory that was to make the bamboo lamps. I had made a series of sketches, of which the first prototypes had been made. We arrived in Hanoi at night and the streets were almost deserted. But the following morning we proceeded to the factory in familiar surroundings, through the traffic of cars, mopeds, bikes and pedestrians and with a distinct lack of traffic rules. For every anarchist, a trip through Hanoi is confirmation that the numerous irritating rules we have here are unnecessary. During the already exciting taxi ride, Carmen Stoicescu received a call from the test lab in Almhült. Product quality is her responsibility. The chair had ben subjected to the first and most severe durability test. In contrast to the team’s expectations, the chair had withstood this test without problems. So I was able to tease Carmen for the rest of the journey. All those IKEA tests were excessive, because my test was just as good and much more efficient, and IKEA could really just trust me and forget about all that hassle.

When we arrived at the factory it turned out that they had only started making the prototypes that morning. This wasn’t such a problem, as we would first be listening to a presentation before entering the factory to see what the possibilities were. Things proceeded as always, the fun really got started when we entered the factory. There were enormous numbers of people working in teams on various products. They were all wearing blue overalls; it was just like a theatre show especially for us. The prototype-makers came from outside the factory and were true craftsmen.

I had devised a series of lamps, inspired by the classic cast iron and steel wire factory lamps we all know. Now they were to be made completely of bamboo, as if they were traditional Vietnamese work lamps that almost perfectly match the bamboo scaffolding that can be seen everywhere around and under construction sites. These gigantic bamboo scaffolds could even be seen around enormous, modern concrete buildings-to-be. In Asia, a scaffolding pipe is made of bamboo. It seemed quite logical to make lamps according to the drawings because their industrial character demands that they are made round and very neatly. After some instruction and when the moulds had been made, the prototype-makers produced almost perfect results. These items were in stark contrast to the shapeless lamp made of seagrass. It is not easy to shape seagrass into a sleek shape so I thought: let’s make it amorphous. The resulting lamp was very characteristic, but a little too extreme.

This time the presentation was in a showroom completely full of lamps, which was good because we were literally sitting among the possibilities they had to offer. One of the lamps was a kind of punched-out lamp that has a classical, lace-like structure. I saw the material and thought that we could perhaps make the double-walled lamps that had been devised for the Jassa collection but had failed. They had failed because the fibres and rings had to be pulled tight in order to create a beautiful interference pattern. The prototypes were quite good and produced nice light but the lamps were a bit clumsy. Brian loved them and had taken one home. He showed photos of the lamp to anyone who was interested. Encouraged by his enthusiasm, it was now a very attractive prospect to make a lamp using this embroidered fabric. From a distance the fabric did not resemble the lamp with tight wires but it was a textile lamp, which we had been thinking about for a while. The lamp-shade was flexible and could be hung up in two ways, assembled and disassembled. It was actually two lamps. I sketched another few lamps but we had run out of time. In less than forty-eight hours we had made a whole series of lamps. And we even had time to take photos of the lamps for a summary, so that everything of importance was recorded for everyone before our departure.

The vases and tableware I had sketched were also being made in Asia but it was not necessary to visit these factories. Karin supervised this process. She did an enormous amount of travelling to compile the collection and to get the products from the factories into the shops.

Glass

The final factory visit I undertook to complete the Industriell collection was a visit to the French glass factory in Arque. They make pressed glass. This is glass that smashes into thousands of pieces if you drop it on the floor. It can also be hardened so that it will break into larger pieces, but in any event it is glass that we have all seen smash on the floor.

Once again, I had devised this collection to be hand-drawn and then to make digital drawings of these sketches. The machines each had twelve stations and in the factory there were several of these machines in a row. I thought I would be able to make twelve different moulds, but this was not possible. The inner form that is pressed into the mould is always the same, and beneath this is a carrousel as big as a child’s bedroom that gradually turns a step further. The machines are industrial monsters that operate day and night, producing enormous quantities of glass products at an enormous tempo. The red-hot glass flows through a channel and from there is poured in a graceful arc into the mould, where it is subsequently pressed into the desired shape at speed and under pressure. A room as big as a house, where the glass is kept red-hot day and night, provides a constant supply of molten glass. The air supply for the burners and the air outlet are regularly switched, so that the air supply entering the burners always flows through the channel that has just been warmed up. So it’s a huge heating-recovery-system, as big as a block of houses. After coming out of the press, pallets, sliders and other ingenious low-tech methods are used to transport the glasses through a cooling tunnel to the quality control, where they are checked by much more modern machines. These tests would be superfluous for our glasses. Every glass that remained intact was good.

Little remained of the idea to make twelve different glasses. The system had just one inner mould and all glasses had to be made from exactly the same amount of molten glass. So it would be almost impossible to make a series of different outer moulds to fit these specifications. Furthermore, the moulds for the glass were extremely expensive. As a result we finally decided to make different glasses using two machines. Our estimation was that these two together, because they are never all always placed in exactly the same position, would give the impression that the glasses are all different.

If a different product of colour of glass has to be made, it takes several hours to change the moulds in the machines as the coloured glass has to be completely removed from the system – this takes seven to eight hours. During the discussion about how we were going to produce the glasses, I suggested that every time the colours were changed, we could use the in-between hours to produce our glasses, or at least to start-up the run of our glass as quickly as possible after a change-over so that we would get the remaining colours from the previous run in our glass, and every glass would be a little different. It took a while before they understood the idea. I focused mainly on the employee involved with environmental aspects, but the response was ultimately negative. This change was too big for the factory. They would have to change their whole routine. I looked at Karin and we decided to let it rest for now. Also because several other problems had arisen in relation to the wall-thickness, whereby we had chosen the thinnest possible and the letters we wanted to add to the underside were not easily realised.

Karin had suggested several times that we should forget the pressed glass, but I was of the opinion that this product fitted perfectly within the theme of handmade mass-production. It was the only remaining, truly mass-produced product in the collection and it was therefore of such importance to keep it. Until this moment I had not been completely aware how massive the production of pressed glass is and how complicated it was to encourage the people involved in such mass-production to do something they would normally not do.

Vases

One of the few products that had survived the in-flight-session on the way home were the hand-sculpted vases. We had made the five mother vases in our own ceramic workshop. They had become kind of ‘Flintstone vases’. There was also a discussion about these vases that had not yet been resolved. Karin thought that two or three mother vases would be enough but I had insisted that we would need to make at least five models. We could always decide later to make fewer.

At a certain moment we had a discussion about the way in which the vases would be produced, packaged, transported and presented in the shops. The problems started with production. They would have to work with five models, but actually they shouldn’t be paying attention to where each different product is in the process, so that the products would be distributed randomly over the pallets. The pallets should subsequently be distributed to shops in the same random way so that it would give the impression that the vases were all different and there was a great deal of choice. We would use just one item number, so there would officially be no distinction between the five different vases. Customers in the shops would make their own individual choice. Everything that normally doesn’t happen at IKEA would happen. Customers would unpack the pallets themselves to get their hands on their favourite shape from the bottom of the pile. Tempers started running high at the thought of all the things that could go wrong, and were sure to go wrong. At a certain point I started seeing the fun of it all, as this is exactly what we wanted to happen when we first started with the Industriell collection. The customer must choose and thereby have the feeling that they are buying a unique product. That was the objective. But now that it was becoming clear what this meant for the logistics and the organisation, most people started panicking a little. The conclusion was that we actually liked it when things went wrong. Who knows, maybe it won’t be so bad when the customer starts choosing and everything becomes a big mess! We embraced the uncertainty.

Democratic Design Days

Shortly before the summer in 2017, our collaboration and part of the collection were presented during the ‘Democratic Design Days’ in Älmhult. This presentation to the world press surpassed that of the Jassa launch between the cornfields in the polder. Journalists had flown in from all over the world and a presentation was given that I could, actually had to, attend. The collaborations that had been completed were discussed and presented and the coming collections and collaborations were announced. Tom Dixon was there as well as a group of super hip fashion designers from the States and a Swedish fashion designer from Los Angeles who designs clothing for pop stars, including Madonna. It was an illustrious group of people.

On this scale, my contribution to our project was a very small piece of a much larger puzzle. As creative director, Marcus had completely disregarded company policy by bringing in as many people as possible with different qualities from all corners of the globe. Instead of being a self-reflecting, gigantic company, it was one that had thrown open the doors, not only to let people take a look inside but also to work together with others. After the official presentation inside, the hundreds of journalists and designers were taken to a barn in the surrounding estates where there were all kinds of things to do, but mainly food and drink were available. It turns out that the latter is, for journalists, an important tradition!

Diary text

I have often talked with Karin about the way in which we would present the collection and collaboration. For us it has been quite an adventure that will hopefully never end and that is certainly worth telling people about. Instead of just the end products, we also found it important to highlight the process and the failures.

For this we had two locations in mind right from the start: the Salone del Mobile in Milan, where we had first met, or even better at our premises during Dutch Design Week, which is always focused on design and creativity, much less on sales and commerce. We embraced the plan to hold the presentation during DDW 2017, long before the collection would be available in the shops. Marcus was also enthusiastic about this and we tried to organise it. Right from the start it was clear that it would have to take place in the gallery space that we normally rent out to young designers and small businesses during DDW. We quoted the rental cost for a comparable amount per square meter and sent it to IKEA-Nederland. They would be funding the presentation. The logic behind this eluded me, as the DDW is a very international event and the collection would be sold worldwide so it seemed more logical to me that head office would organise and finance it. After months of wrangling, and despite everyone’s enthusiasm, it was impossible to get any budget. We hadn’t managed to find the right string to pull. The next day we rented all the spaces to young designers, which in hindsight was actually also the most fun. Making a presentation, in which the content and the process would serve as starting point, would have been a lot of work so it actually worked out quite well that it didn’t go ahead.

When we returned from holiday, Karin mailed us that Marcus actually wanted to organise a presentation during DDW after all. Goodness knows what had happened or changed in the meantime. The gallery space was completely rented out so we had to look for a new location. In order to keep things clear, we normally don’t host any presentations during DDW outside the gallery space and the event space. Our showroom is completely dedicated to the exhibition of our own collection. After giving it some thought, we decided that that the presentation could actually take place in our own showroom after all. It may be for a different company, but I have designed the collection.

Karin arrived in Eindhoven with a group of great young guys who would take care of the marketing for the project. We came to the conclusion that the theme would be the process and that we would tell the whole honest story of our collaboration. To start with, I would write a kind of designers diary about all that had happened from my perspective since the very first time I met Karin in 2015 until now (DDW 2017).

We have now transformed this text into an (or this) IKEA Eek publication.

Please click here to download the PDF.

Click here for an overview of all products.

Download high resolution images by clicking the following link.

This post is also available in: NL

« Back to blog